OStack Reads: Why writing is thinking (and why AI can't do it for you)

Mark Levy's 'Accidental Genius' is an urgent reminder that the messy, private, thinking-on-paper stage of writing is essential in a world of people desperate for AI shortcuts.

The release of ChatGPT-5 last week was widely regarded as a big, fat disappointment.

People who use this tool all day seem to be miffed because the AI chatbot is fundamentally the same as it’s always been: a limited text-manipulation machine, still capable of glaring mistakes, and still a long way from the dream personal assistant the hype machine would have you believe.

Look, it’s not that using AI is bad per se. But what drives the hype cycle is a modern illness of tech FOMO: the idea that if you’re not across the latest social media trend, the new iPhone camera specs, or as is now the case: the ways AI supposedly threatens your job, you’re a Luddite or out of touch.

No wonder the US stock market is so dependent on a handful of Big Tech giants. We’ve built an economy desperate for innovation for its own sake, instead of critically thinking about how to add value through our work and how tech can help. With ChatGPT, too many people assume the tech is valuable, then get frustrated when they fail to uncover that value.

Even the way AI sucks up to us is getting a bad rap!

Still, here we are: everyone’s using an AI chatbot. Myself included. When I launched my solo gig in January, I made a serious effort to use these tools for writing support, research, clarifying strategic thinking, and analysing long interviews and reports. The results have been mixed. My conclusions so far:

Within strictly limited parameters — detailed prompts and very careful information input — AI can be useful and time-saving. More on this here.

For most people, using AI as a substitute for thinking and writing will make you a worse writer and a worse thinker. That’s because the real value of writing isn’t in typing sentences — it’s in the mental work of shaping half-formed ideas into something worth saying. If you hand that step to a machine, you’re skipping the part that actually builds your skill and sharpens your judgement.

“Oh Omar, you corporate whore!” I hear you say, “AI threatens your lavishly lucrative business as a freelance ghostwriter for media and advertising leaders!”

Well, yes — but not because AI is better than me. Don’t you think I’ve tried to feed it examples of my work to spit out 800-word essays in seconds? Of course I have. It doesn’t work, for two reasons:

1. The computing juice isn’t being squeezed enough. GPT-5 uses a unified model system with a dynamic router that automatically decides whether to activate the fast, efficient sub-model (gpt-5-main) or the deeper gpt-5-thinking model, based on the complexity of your prompt or explicit cues like “think hard about this.” In practice, when usage limits — especially on free or lower tiers — are reached, users are automatically redirected to lighter variants like gpt-5-mini, resulting in a noticeably diluted output compared to the richer responses from the full model. Even if it’s not obvious to the average reader that you’ve AI-ed your writing, most will have at least a vague sense something is off, artificial, or contrived. And repeated AI-written output will, eventually, make you seem off, artificial, or contrived.

2. Using AI for writing like this falls foul of a fundamental misunderstanding of what writing is. The mistake is thinking your brain contains a ready-made set of ideas that can be uploaded into an AI, which will then craft them into perfectly formed prose. In reality — and I hate to break it to you, fellow human — you don’t actually know what you think. Writing is the tool humans have used for centuries to help formulate and clarify thinking, not just to express it. This is why keeping a diary can be so powerful, even though it may never see the light of day.

So the point isn’t that AI will take my job. The point is that too many people — in business, media, and marketing — think the job of writing starts and ends with publishing words. It doesn’t. Writing is the first step, not the last. It’s the thinking tool you use to shape ideas before you decide which ones deserve daylight. Skip that step, and all you’re doing is polishing whatever half-formed notion happened to land in your lap. That’s why I use — and help clients use — writing not just to make things sound good, but to think well in the first place.

And if you don’t think being able to think well is important, in a time when businesses are apparently desperate to automate whatever they can, then you’re really not paying attention. This isn’t the 20th century, when you could build a career as an expert in operating a particular machine or system of machines — and yes, that includes being a “super-duper AI prompt master.”

We are now, in a world of free or cheap tech, in the business of harnessing and leveraging ideas. And you just so happen to have a squishy supercomputer between your ears that’s perfectly built for the job — if you can learn to use it properly.

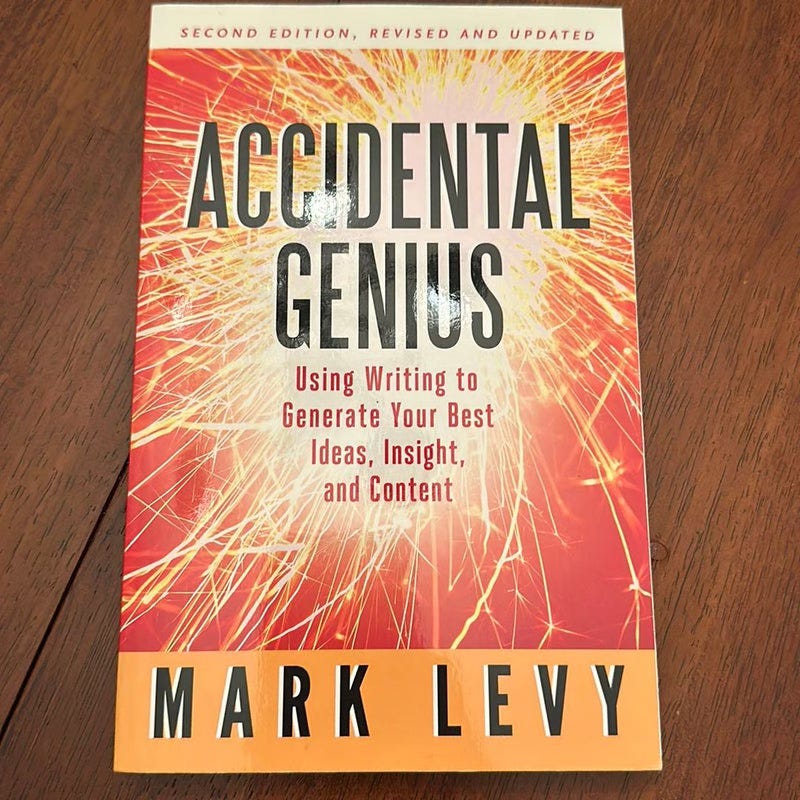

Enter Accidental Genius

If you’re not convinced, read Accidental Genius by Mark Levy. This book introduced me to a technique I now use whenever I need to think through a problem or brainstorm ideas: freewriting.

Levy defines freewriting as “writing as fast as you can for a set period of time without stopping, editing, or censoring yourself.” The idea is to bypass your internal editor — that part of your brain that wants every sentence to be clever or precise — so you can actually get to the raw material of your thinking.

What is it? It’s simply setting a clock for a few minutes and writing down anything that pops into your mind. Just don’t stop to think or edit — ever. At first it seems monumentally stupid, but after a while something interesting happens where stuff just seems to pour out of you.

It’s a fascinating process and I do this before I write almost any opinion essay or need to brainstorm ideas for a problem.

Levy lays out six rules for effective freewriting, including:

Write quickly and continuously

Work against a time limit

Go with the first words that come

Don’t worry about spelling or grammar

If you get stuck, repeat the last word you wrote

Why does this work? Because the biggest barrier to good ideas is not ignorance, it’s inhibition. We interrupt ourselves before our thoughts can fully form. Levy’s technique forces you to get past that barrier and, crucially, gives you a written record you can mine for insight later.

When I use freewriting with clients, it’s often the turning point in a project. A muddled brand strategy suddenly snaps into focus. A half-baked marketing idea gets the extra dimension it needs. A messy pitch deck finds its through-line.

Freewriting isn’t just for “creative types.” It’s for anyone whose job depends on solving problems, spotting patterns, or coming up with ideas worth sharing. In other words: almost everyone in business.

Who This Book Is For

Accidental Genius is for people who think they’re “bad writers” but who actually just don’t have a process for thinking on paper. It’s for founders and execs who’ve outsourced so much comms work that they’ve forgotten how to articulate their own ideas. It’s for strategists who live in slide decks and bullet points but never give themselves time to explore a thought before packaging it.

And it’s for anyone feeling the pressure to use AI for every content-related task, without realising that the most valuable content you create might never be published. It might just be the notes you use to figure out what you think — before you hand anything over to a bot, a colleague, or a paying client.

Length: 208 pages

Time to read: Around 3–4 hours at a steady pace. You can grasp the basic freewriting method in under an hour, but the full examples, applications, and deeper guidance reward a slower read.

One-liner pitch: A practical manual for using freewriting to unlock ideas, solve problems, and sharpen your thinking.

Best for: Executives, strategists, entrepreneurs, and anyone who wants clearer, more original ideas — even if they think they “can’t write.”

Thanks for reading. But who wrote this?

I’m Omar Oakes: a journalist and strategist who’s spent the last decade picking apart how media, marketing, and content actually work — not how they pretend to. I bring together a rare mix of network, voice, and track record: building publications, growing audiences, and challenging the stories this industry tells itself.

Through my consultancy, oomph., I help agencies, media owners, and senior marketers sharpen their positioning, craft industry-leading narratives, and turn complex issues into content that actually moves people.

I have no plans to put this newsletter behind a paywall. I earn my living as a paid columnist, ghostwriter and freelance journalist covering advertising and media. This Substack is where I share the same ideas, challenges, and provocations I bring to my clients, because if we want a better media industry, someone has to start the conversation.

📩 Reach me: omar@oomphoomph.com

🔗 More about me: https://www.linkedin.com/in/omaroakes/